Prologue

My path to Computer Science was somewhat irregular. From I974 to 1983 I studied medicine in Utrecht, taking a break between 1977-1980. End of 1981, just before my first year of internships, I was diagnosed with a rare type of macular degeneration. I scrambled though the first year of clinical training, but after completing my masters (‘doctoraal’) I went to Stanford for a second opinion and had to conclude a medical career was no longer an option. While in California my brother-in-law Yuda, who was doing a PhD in computer science at UCLA, gave me his Pascal book (the trending programming language at the time). After recovering from surgery for macular detachment I enrolled for one year in the computer-science program of the University of Utrecht, taking as many courses as I could. End of 1984 I did an internship in Medical Informatics at the University of Leiden. On 1 February 1985 I was hired there and my academic career had kicked off.

Research

In Leiden I worked on a method for generalising decision trees, using data about prostate cancer. After a year it become clear medical-informatics research had no future in Leiden, and I applied in 1986 for a job as research assistant at the University of Amsterdam in the group of Bob Wielinga, who had just acquired project funding in one of the first EU research programs. Expert systems, one of the first forms of AI, were a key research topic at that time, and Bob worked on a systematic approach for building such systems named KADS, which gained world-wide popularity. The discipline of ‘knowledge engineering’ provided me with ample research opportunities, and the unique atmosphere in Bob’s SWI group was a significant factor in my academic development. I worked on a series of EU projects in the knowledge-engineering area and in 1992 had written a sufficient number of articles to complete a PhD. My thesis contained the seminal journal article about KADS and was the basis for the first KADS book.

After my thesis I continued as a post-doc, wrote several successful EU grant proposals and started working on ontologies. My first PhD student Gertjan van Heijst published a highly cited article one this subject. I was lucky to work with colleagues such as Frank van Harmelen and Dieter Fensel. In 1997, at the age of 41, I finally got tenure as associate professor at the University of Amsterdam. By then I had decided to shift my research focus to web data, and to this end I wrote, together with Hans Akkermans and other colleagues, the CommonKADS textbook, more or less as my final word on this subject.

In the second half of the nineties the Web developed quickly, and knowledge engineering took on a different form: from single isolated applications to distributed intelligent systems. Bob and I, together with Jan Wielemaker, Jacco van Ossenbruggen and many other colleagues, started working on using background knowledge to make web search more intelligent (‘semantic search’). As application domain we chose cultural heritage, i.e. museum, archive and library collections. The diverse and knowledge-intensive nature of this domain provided a challenging testbed for our methods. This research can be viewed as part of the Semantic Web initiative, kicked off in 1999 by the inventor of the World-Wide Web, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. As part of this initiative, the World-Wide Web Consortium started a number of standardisation groups. This became an important (and time-consuming) sideline of my work, see the separate section below.

In 2003 I was appointed as full professor of Intelligent Information Systems at the Department of Computer Science of the Vrije Univesiteit Amsterdam (VU). Frank van Harmelen and I joined forces and together we headed the VU Semantic Web group. Over time, a number of former UvA colleagues joined as well, including Bob Wielinga. The group flourished, also with the help of a stream of externally funded projects. In 2007 Vrij Nederland (an influential Dutch Periodical) dedicated a ten-page article to the VU Semantic Web group. The work on semantic search in heritage collections culminated in the Multmedian E-Culture demonstrator, using data from collections such as the Rijksmuseum and the Louvre.

From 2007 on the semantic-web research diversified, also under the influence of our new colleague Lora Aroyo. New projects looked, amongst others, into audiovisual archives, historical events, and TV viewing, with research topics such as open data, semantic annotation, ontology alignment, and recommendations.

For more information see the pages ‘Talks & Press‘ and ‘Publications‘. In 2014 I became head of department, and in 2016 dean of the Faculty of Science, so my research activity slowly petered away. I have continued to supervise PhD students, which is one of the most difficult but also most rewarding research activities. For the Liber Amicorum of Bob Wielinga I wrote a short article about the lessons I learned from him on this subject: ‘The Art of PhD Supervision’.

W3C work

The World-Wide Web Consortium (W3C) was set up in 1994 by Tim Berners-Lee and colleagues. Its goal was and is to develop and maintain standards and guidelines to ensure an open, accessible and secure World-Wide Web. These standards ensure that nobody can ‘own’ the Web. W3C has also been instrumental in setting standards for accessibility, which ensure that the Web is inclusive and has no barriers, for example for people with disabilities. The W3C accessibility guidelines have now been adopted in national and international law.

As part of the Semantic Web effort W3C formed at the end of 2001 a working group to standardise a ‘Web Ontology Language’. Several proposals for such a language already existed, including one from my colleagues Frank van Harmelen and Dieter Fensel. Jim Hendler, the chair of the group, asked me to become his co-chair. My positive answer had a much larger influence on my academic life than I had foreseen.

The Web Ontology working group met every week for two years: 90 minutes, with 30+ people from different time-zones on a audio-teleconference. Chairing it was a tough task, with so many strong and diverse opinions around the table, but I must admit I enjoyed it a lot, although it came on top of my regular university duties. Finding consensus in such a group is almost an art. Dan Connolly, an old hand in this process, helped Jim and me to learn this art. Basically, he took everybody and every comment seriously, even if it seemed silly. In that way you build trust and you improve your own empathy. When the first OWL standard was completed in February it 2004 I was proud of all the things we achieved.

W3C asked me to chair three other groups. In the period 2004-2009 I chaired the Semantic Web Best Practices and Deployment Working Group (with David Wood as co-chair) and the Semantic Web Deployment Working Group (with Tom Baker as co-chair ), Finally, I chaired from 2011-2014 the RDF Working Group, which produced an update of the RDF specification.

Education

I lectured my first course in 1995, as a post-doc. I am not a natural teacher and it took me some time to reach an adequate professional level. Having said that, I enjoyed teaching a lot. Next to specialised master courses I have teaching a range of bachelor courses, including Web Technology, Software Engineering and Databases. It is my firm belief that a self-respecting academic should be able to teach every first-year bachelor subject.

Later on in my career I also become involved in education management. I was responsible for the first regular VU bachelor program taught in English, which started in 2012. As dean (see next section) I set up a collaboration with University of Twente to make it possible to get an engineering degree at the VU campus, something which was missing in the Noth-Holland area.

The two short notes below contain some of the lessons I learned about education and education infrastructure:

Research integrity is a subject close to my heart. During my time as dean I started to give a lecture on authorship in the research-integrity course of the faculty, as more than 50% of the reported integrity problems concern an authorship-related issue.

Dean Faculty of Science & Vice Rector

In 2016 I became, somewhat to my own surprise, Dean of the VU Faculty of Science. From 2019 till 2022 I also served as Vice Rector of the university. Some academics look down upon such a management job, but I found it interesting and rewarding. An important factor for this was (and is) the collegial working atmosphere within the faculty, devoid of the usual power struggles that can make academic environments so toxic.

When I became Dean there were in fact two separate faculties, which we merged into one large faculty. The fact that this process was smooth and uneventful is both unusual for academia mergers as well as a testament to the afore mentioned atmosphere. I remember some calling the Faculty of Science “the best kept secret of the VU”, with in 2020 more than 10,000 students and 40 educational programs. The faculty is home to almost all science disciplines, including physics, chemistry, mathematics, computer science, biology, earth science, environmental science, and health science. Our close cooperation with the Amsterdam University Medical Centre meant that my medical background was not entirely useless :).

UvA-VU collaboration

Another merge ended in tears. In 2016 the plans to crate common housing facilities for the science faculties of the VU and of the University of Amsterdam were in their final stage. The plans made a lot sense: investments in infrastructure for science are costly, and it would have been wise to refrain from duplicating those in such a small geographical area. Unfortunately, these efforts stranded in April 2017 due to inter-university struggles. Prejudice and sentiments triumphed over ratio. My UvA colleague Peter van Tienderen and I wrote a short note about this frustrating outcome: “On the failure of the joint housing plans of our science faculties.”

COVID-19

In March 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many parts of life, including academic life. Education became challenging, especially for our science programs due the need for practicals. Looking back, it is incredible how everyone, staff and students alike, quickly adapted to the new reality. Within days after every new lockdown or new government rules, workarounds were created to minimise the impact. A team effort, if ever there was one. The role of support staff (e.g., roster planners, lab technicians) is often undervalued in academia, but proved critical here.

Sector plans

The Science deans in The Netherlands meet regularly to discuss topics of importance to all of us. The atmosphere is collegial in the true sense of the word; our dinners afterwards were memorable. But foremost: together we got things done. In particular, we managed to secure substantial and structural extra funding for the science disciplines: in 2019 for physics, chemistry, mathematics and computer science, in 2022 for biology and earth & environmental sciences. I’m still proud of the fact that I took the initiative to bring the fields of earth sciences and environmental sciences in The Netherlands together for this purpose, as this increased the political chances to secure this funding significantly; it paid off in the end.

VU & University of Twente

In The Netherlands university-level education in engineering is mostly restricted to the so-called “technical” universities: Delft, Eindhoven and Twente. However, students nowadays mainly choose bachelor programs close to home, also due to the poor housing situation. At the same time, society is asking for more engineers. For this reason we started in 2017 a collaboration with University of Twente to offer bachelor programs in engineering at the VU campus in Amsterdam. In 2019 this resulted in a joint Mechanical Engineering bachelor. Students travel twice a month for two days to Twente (which has facilities for staying over) for practical work; for the remainder they study in Amsterdam. The program was an immediate success. In 2022 a second joint program was started, in Creative Technology. A remarkable piece of cooperation between two universities!

After my official retirement I stayed on for an additional two years to act, on behalf of both universities, as chair of the joint steering committee. As part of this work I wrote a vision for 2030 (in Dutch).

Varia

When my six-year term as dean ended my colleagues asked Ernst van der Kwast to write something about me. He entitled it “The visionary cyclist” (in Dutch).

Here are a few documents I wrote as dean:

- VU vision on Recognition & Rewards (“Erkennen en Waarderen”), 2021

- VU policy w.r.t Accessibility of Web Content (in Dutch), 2018

- Three key aspects of leadership (in Dutch), 2017

Here are some interviews which appeared in the university magazine Ad Valvas (all in Dutch):

- ‘Discussie bètasamenwerking gaat niet meer over argumenten‘ (March 2017)

- ‘Dit zegt veel over de slagkracht van het UvA-bestuur‘ (May 2017)

- ‘Het beste gehandicaptenbeleid is geen beleid‘ (February 2018)

- ‘Bètafaculteit wil ook vacatures voor alleen vrouwen‘ (July 209)

- ‘De discussie over impact factors in achterhaald‘ (August 202)

- ‘Ik ben van de radicale transparantie‘ (April 2023)

Acknowledgements

I have been extremely lucky (and this is putting it mildly) in getting help and support from friends and colleagues at critical points in my academic career. I feel deeply privileged to have been able to do this work.

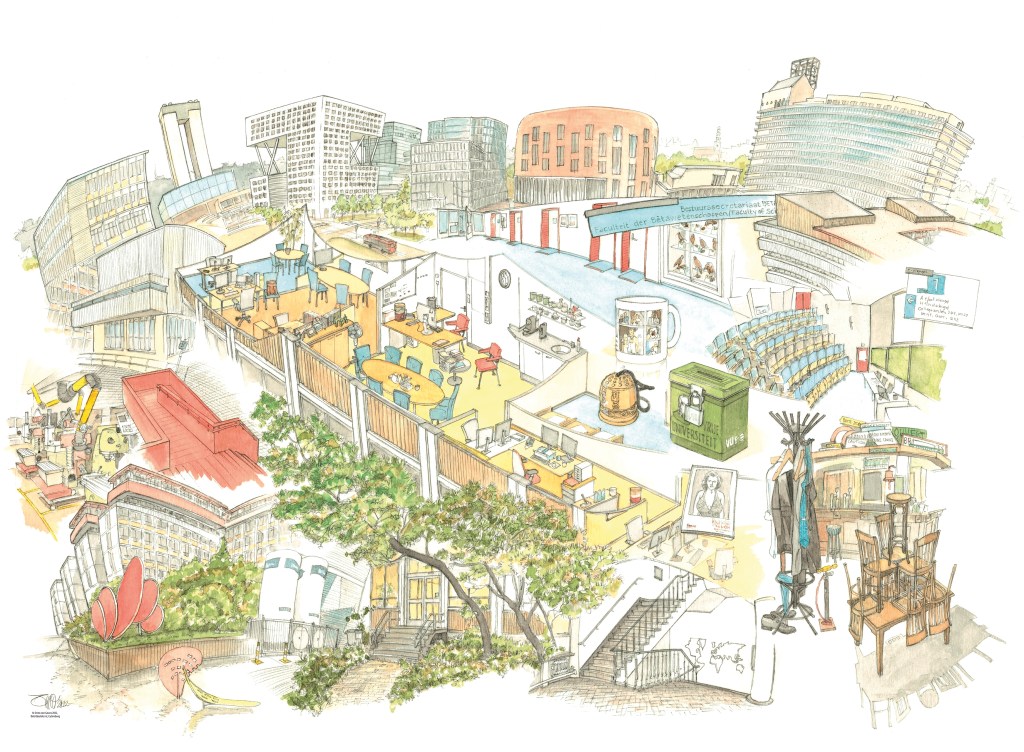

Below is the drawing I got from my colleagues when I retired as dean, showing many of the places at the VU Science Faculty dear to me. Part of this drawing is used as the banner of this website.